In our recent work on the revised texts of Wilder’s Pioneer Girl, we have had some pleasant discoveries that make the job enjoyable. For example, in trying to determine why the Brandt manuscript is missing page 2, we discovered that the Lane Papers at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library also contain a six-page Pioneer Girl fragment, page 2 of which fits seamlessly into that hole in Brandt. Sweet!

Careful perusal of the fragment shows that its pages 3 through 6 are exact duplicates of the same pages of the Brandt manuscript. And, in fact, Hoover archivist Nancy DeHamer pointed out that pages 3 through 6 of Brandt were actually carbon copies, while this fragment contained the originals. Because page 2 fit so exactly into the hole in Brandt, we reasoned that these six fragmentary pages are actually the first edited rendition of Wilder’s Pioneer Girl; only the title page is different.

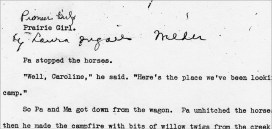

And what a difference it is! The name of this fragment is “Prairie Girl.” Lane has written “Pioneer Girl” above it and added Wilder’s name in longhand, a change that was duly made on the title page of the Brandt manuscript. She also made two small corrections in the text, changing Wilder’s passive voice, “sister Mary and I were put to bed,” into active voice, “she [Ma] put my sister Mary and me to bed.” Such is what a good copyeditor does. More intriguing was the title change.

And what a difference it is! The name of this fragment is “Prairie Girl.” Lane has written “Pioneer Girl” above it and added Wilder’s name in longhand, a change that was duly made on the title page of the Brandt manuscript. She also made two small corrections in the text, changing Wilder’s passive voice, “sister Mary and I were put to bed,” into active voice, “she [Ma] put my sister Mary and me to bed.” Such is what a good copyeditor does. More intriguing was the title change.

Had Wilder originally called her manuscript “Prairie Girl” and had Lane changed it? Or had Wilder left it unnamed and objected to Lane’s assignment of “Prairie Girl”? Or had one or the other of them decided that “Prairie Girl” was not appropriate for the Wisconsin portion of the manuscript and substituted “Pioneer Girl,” which covered all geographical frontiers. My guess is the latter. Wilder truly loved the prairie, its flowers and wildlife, and, I think, considered herself a prairie girl even after moving to the Missouri Ozarks. Later, as you recall, she planned to call her last book in the Little House series “Prairie Girl,” giving that title to her preliminary outline. When that outline generated two books rather than one, “Prairie Girl” as a title again fell through the cracks in favor of Little Town on the Prairie and These Happy Golden Years. So, I lean toward the idea that Wilder originally titled her memoir “Prairie Girl” and changed it to the more generic “Pioneer Girl,” but we will never know for sure.

Nancy Tystad Koupal

The first phase of our project came to fruition in 2014, with the publication of Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, edited by Pamela Smith Hill. And, as you all know, that book found both a national and international audience and went on to become another bestselling volume by author Laura Ingalls Wilder. Moreover, its financial success gave the Pioneer Girl Project team the resources to plan three additional books. The second is Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder, published in May 2017.

The first phase of our project came to fruition in 2014, with the publication of Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography, edited by Pamela Smith Hill. And, as you all know, that book found both a national and international audience and went on to become another bestselling volume by author Laura Ingalls Wilder. Moreover, its financial success gave the Pioneer Girl Project team the resources to plan three additional books. The second is Pioneer Girl Perspectives: Exploring Laura Ingalls Wilder, published in May 2017. original handwritten autobiography was drawing to a close in 2014. The project team could see that many questions remained unanswered about Wilder as a person and about Wilder as a writer—and especially about the relationship between Wilder and her daughter Rose Wilder Lane. Because we had been studying the text of the handwritten Pioneer Girl so meticulously and comparing it to the typed and edited versions, it became clear that there was indeed something special about that mother/daughter, writer/editor relationship. This complex relationship reveals itself more fully as we examine Lane’s edits to her mother’s writing and then evaluate the evolution in Wilder’s response. Clues about this process abound in both the nonfiction and fiction texts, drafts, discarded pages, and other materials held at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and elsewhere.

original handwritten autobiography was drawing to a close in 2014. The project team could see that many questions remained unanswered about Wilder as a person and about Wilder as a writer—and especially about the relationship between Wilder and her daughter Rose Wilder Lane. Because we had been studying the text of the handwritten Pioneer Girl so meticulously and comparing it to the typed and edited versions, it became clear that there was indeed something special about that mother/daughter, writer/editor relationship. This complex relationship reveals itself more fully as we examine Lane’s edits to her mother’s writing and then evaluate the evolution in Wilder’s response. Clues about this process abound in both the nonfiction and fiction texts, drafts, discarded pages, and other materials held at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and elsewhere.