In her final Little House books, Laura Ingalls Wilder showcased her independent spirit and almost defiant self-reliance. For instance, in These Happy Golden Years, Laura—clad in an attractive brown dress—joins Almanzo on a buggy ride behind the colts. When Almanzo boldly puts his arm around her, Laura immediately startles the horses with the whip, causing them to bolt. “You little devil!” Almanzo says as he uses both hands to get the horses back under control. He then challenges her: “Suppose they had run away,” he says, but she replies that there was nothing for them to run against. “‘Just the same!’ Almanzo began, and then he said, ‘You’re independent, aren’t you?’ ‘Yes,’ said Laura” (THGY, pp. 166, 168). In her study of the pioneer heroines of regional fiction, Ruth Ann Alexander characterized these fictional protagonists as “usually quite independent of their mothers, they identify with male activities in homesteading, ranching, and small-town life, and they triumph through exercising their own wits and resources.”1 In her autobiography and her novels, Wilder portrayed herself with all the traits of this classic heroine of adolescent pioneer fiction.

In her final Little House books, Laura Ingalls Wilder showcased her independent spirit and almost defiant self-reliance. For instance, in These Happy Golden Years, Laura—clad in an attractive brown dress—joins Almanzo on a buggy ride behind the colts. When Almanzo boldly puts his arm around her, Laura immediately startles the horses with the whip, causing them to bolt. “You little devil!” Almanzo says as he uses both hands to get the horses back under control. He then challenges her: “Suppose they had run away,” he says, but she replies that there was nothing for them to run against. “‘Just the same!’ Almanzo began, and then he said, ‘You’re independent, aren’t you?’ ‘Yes,’ said Laura” (THGY, pp. 166, 168). In her study of the pioneer heroines of regional fiction, Ruth Ann Alexander characterized these fictional protagonists as “usually quite independent of their mothers, they identify with male activities in homesteading, ranching, and small-town life, and they triumph through exercising their own wits and resources.”1 In her autobiography and her novels, Wilder portrayed herself with all the traits of this classic heroine of adolescent pioneer fiction.

In Pioneer Girl, Wilder is even more overtly independent. During thunderstorms in the summers of 1884 and 1885, she separated from her mother and sisters who huddled in the cellar and aligned herself with the riskier behavior of her father, who stayed outside to watch the storms approach. “I didn’t like to go into the cellar,” she wrote, “and I wanted to see the storm. I thought I could get to safety as quickly as Pa could. And I proved it.”2 While Laura does not insist on staying outside with Pa in Wilder’s draft of These Happy Golden Years, she does express “a strange delight in the wildness and strength of the storm winds, the terrible beauty of the lightening [sic] and the crashes of thunder.”3

Nancy Tystad Koupal

1.) Alexander, “South Dakota Women Writers and the Blooming of the Pioneer Heroine, 1922–1939,” South Dakota History 14 (Winter 1884): 306.

2.) Wilder, Pioneer Girl: The Revised Texts, ed. Nancy Tystad Koupal et al. (Pierre: South Dakota Historical Society Press, forthcoming 2021), p. 438.

3.) Wilder, “These Happy Golden Years” manuscript, p. 202, Rare Book Collection, Detroit Public Library, Detroit, Mich.

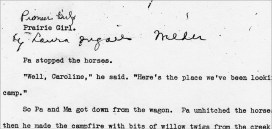

And what a difference it is! The name of this fragment is “Prairie Girl.” Lane has written “Pioneer Girl” above it and added Wilder’s name in longhand, a change that was duly made on the title page of the Brandt manuscript. She also made two small corrections in the text, changing Wilder’s passive voice, “sister Mary and I were put to bed,” into active voice, “she [Ma] put my sister Mary and me to bed.” Such is what a good copyeditor does. More intriguing was the title change.

And what a difference it is! The name of this fragment is “Prairie Girl.” Lane has written “Pioneer Girl” above it and added Wilder’s name in longhand, a change that was duly made on the title page of the Brandt manuscript. She also made two small corrections in the text, changing Wilder’s passive voice, “sister Mary and I were put to bed,” into active voice, “she [Ma] put my sister Mary and me to bed.” Such is what a good copyeditor does. More intriguing was the title change.